To view this press release click here

- From an economic standpoint, the effective burden on mortgage holders has not risen significantly in recent years, and for some borrowers, it has even declined.

- Credit losses in this segment remain extremely low by both historical and international standards.

- The proposal introduces clear discrimination—both among mortgage borrowers themselves and between mortgage borrowers and other types of borrowers.

- The proposal involves retroactive intervention in existing contracts and does not meet accepted international standards.

In recent years, the average monthly repayment on new mortgages has increased, reflecting both the rise in housing prices and changes in the broader macroeconomic environment. This increase has been most pronounced among higher‑income households and among those who took out mortgages during 2021–2022—a period that also saw double‑digit growth in housing prices.

Against this backdrop, the National Economic Council in the Prime Minister’s Office has put forward a proposal to subsidize mortgage borrowers (hereinafter: “the proposal” or “the Council’s proposal”). The proposal has not been formally submitted to the Bank of Israel, nor has it been discussed with the Bank’s professional experts. However, based on information available to us, the main elements of the proposal appear to be as follows:

- A financial subsidy would be granted to existing mortgage holders.

- The size of the subsidy would depend on the real increase in mortgage repayments between 2022 and 2025, as well as on the property’s purchase value at the time of acquisition.

- The subsidy would be financed through a levy imposed on commercial banks.

- The estimated total cost of the subsidy is approximately 3 billion shekels.

From the Bank of Israel’s perspective, this proposal lacks any economic rationale. In contrast, the potential damage to Israel’s economy, its reputation, and its international standing could be substantial.

Although, as noted, the details of the proposal have not been formally conveyed to the Bank, we believe it is important to clarify our position on the matter.

First, the underlying assumption of the proposal—that the burden on mortgage holders has risen significantly—is not supported by a comprehensive analysis of the data. Assessing borrower hardship solely by looking at the size of monthly repayments, while ignoring changes in borrower income, is neither professional nor economically sound. The correct way to measure borrower burden is by examining the ratio between monthly repayments and borrower income (the PTI ratio). The higher this ratio, the lower the borrower’s disposable income after repayment, and the heavier the burden.

An analysis conducted in 2023 of changes in the PTI ratio shows that, after accounting for income growth among borrowers, the debt burden for those who took out mortgages before the interest‑rate increases has actually declined—not risen.

|

Year of borrowing |

PTI |

New unequivalized PTI |

New PTI (equivalized) |

Change in PTI (equivalized) |

|

2017 |

25.8 |

28.8 |

20.4 |

-4.9 |

|

2018 |

25.7 |

29.8 |

22.1 |

-3.3 |

|

2019 |

25.9 |

29.3 |

22.4 |

-3 |

|

2020 |

25.9 |

29.6 |

24 |

-1.7 |

|

2021 |

26.1 |

32.9 |

27.2 |

0.3 |

|

2022 |

26.4 |

29.4 |

27 |

1.1 |

It should be noted that this analysis was conducted during 2023, when the interest rate stood at 4.75%. Since then, the rate has been reduced by 25 basis points, while household incomes have continued to rise—meaning that the analysis overestimates the increase in repayment burdens.

In addition, a quick review of more recent data shows that, in nominal shekel terms, between January 2022 (just before the start of the interest rate hikes) and April 2025, the average monthly mortgage payment rose by approximately NIS 960. Over the same period, the average salary for a full‑time employee increased by about NIS 1,880—nearly double the rise in monthly mortgage payments.

Similarly, private consumption (as measured by nominal credit card spending) has grown at a comparable pace among households with mortgages and those without. Between January 2022 and April 2025, average spending by mortgage holders increased by 27%, while spending among those without mortgages rose by 30%. This is a negligible difference over the period, and indicates that the spending capacity of mortgage holders has not been materially affected relative to the general population.

These figures demonstrate that, relative to income, the overall burden on mortgage borrowers has remained stable—and for some, has even declined.

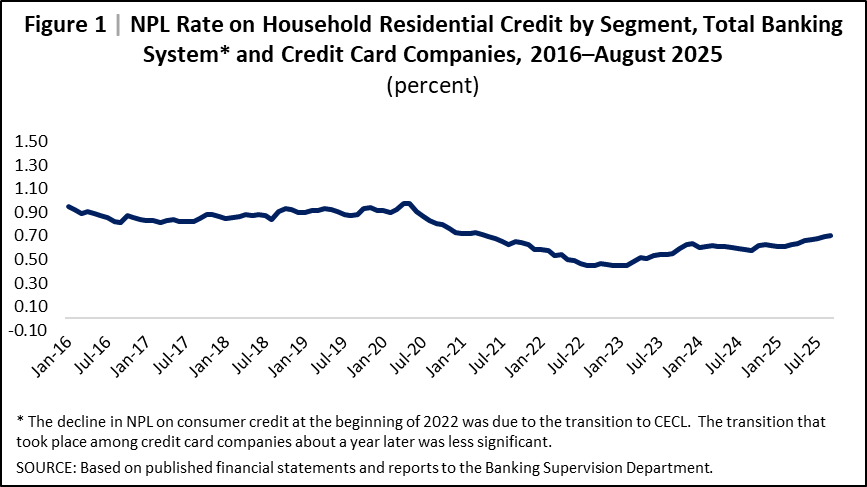

This conclusion is further supported by the relatively low level of credit losses in this segment, which currently stand at just 0.7%—a historically low figure.

The easing of the burden on mortgage borrowers has also been supported by a range of proactive measures taken by the Bank of Israel in recent years. As early as June 2023, the Bank formulated assistance principles that were adopted by the commercial banks, including measures to reduce the debt burden on mortgage holders. Following the outbreak of the war on October 7, 2023, and throughout its duration, the Bank of Israel developed frameworks that were implemented by the banking system. Among other things, these included the deferral of mortgage payments—without interest or fees—for a wide range of customers directly affected by the war, as well as for reservists. After these frameworks concluded, the Bank of Israel introduced an additional plan in April 2025, which was likewise adopted by the banking system. Under this plan, the banks will provide approximately NIS 3 billion in financial relief to their customers over two years, including through concessions on mortgage products.

Taken together, these measures demonstrate that, at the macroeconomic level, there is no professional or data‑based justification for any step involving government subsidization of mortgage borrowers.

Moreover, the proposed subsidy creates clear inequities—both among mortgage borrowers themselves and between mortgage borrowers and other types of borrowers. For example, many mortgage holders have already refinanced their loans, extending repayment periods to reduce their monthly payments. These borrowers would not be eligible for assistance, despite having taken active steps to manage their debt burden—steps that, while lowering monthly payments, increased total interest costs over the life of the loan.

The proposal also discriminates between mortgage borrowers and those who hold other forms of credit, such as consumer loans. In this context, it should be noted that whatever signs there are of financial stress in the credit market are more evident among consumer borrowers, where a modest increase in credit losses has been observed—though still at low levels by both historical and international standards.

Additionally, the proposal creates an imbalance between mortgage borrowers, who have benefited in recent years from rising property values, and renters, who have not.

Finally, the idea of imposing a tax on banks to retroactively finance subsidies for mortgage borrowers is highly problematic and inconsistent with the norms of developed economies. Legislation that obligates a commercial company to subsidize discounts on products it sells is questionable in itself—especially when the obligation applies to products that were sold in the past. The fact that the subsidy would be funneled through the state via a taxation mechanism, rather than transferred directly from banks to consumers, does not mitigate the severity of the measure.

In practice, the proposed tax would be directly linked to the volume of mortgage lending and the increase in repayments, effectively forcing commercial banks to retroactively subsidize mortgage products they have already sold.

The mechanism outlined in the proposal—first imposing a tax equal to one‑third of the banks’ excess profits, and then using those tax revenues to subsidize mortgage borrowers—does not resolve the underlying issues. Given that the distribution of eligible borrowers across banks differs from the distribution of excess profits, the proposal would, in effect, use the profits of one bank to subsidize the customers of another. Such an approach is far removed from the principles of a free and developed market.

In conclusion, this is a measure from which the benefits are doubtful and the potential harm is significant. It is not supported by a structured professional analysis or by data‑driven economic calculations, and it does not align with the norms and standards observed in advanced economies.