- Distributing dividends from unrealized earnings increases, by more than threefold, a company’s probability of encountering a debt restructuring proceeding.

- The increased risk is not priced into yield spreads of corporate bonds for companies that distributed such dividends and is not reflected in their bond ratings.

- The findings of the research may lend support to the proposal of the Ministry of Justice and the Israel Securities Authority to amend the Companies Law, with the goal of preventing the distribution of dividends from unrealized earnings.

Research conducted by Nadav Steinberg of the Bank of Israel, Dr. Ilanit Gavious of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, and Dr. Ester Chen of the Peres Academic Center, deals with the ability to recognize unrealized revaluation earnings—a major pillar of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)—and focuses on a topic that has not been examined to date: does the distribution of dividends from such earnings impact a company’s risk of default?

The motivation to examine this question is related to the conflict of interest created by dividend distributions—for shareholders it has the utmost importance, while for creditors it reduces the firm’s value and thus increases the value of the implicit put option and the probability of default. The literature indicates that corporate executives are attentive to shareholders and thus seek to maintain a smooth dividend policy: when profits are increasing, they may increase the dividends as well, in order to maintain the same payout ratio. It also indicates that companies use their dividends—particularly a smooth distribution policy—to signal their quality to the market.

As companies strive for a smooth dividend policy, and as the IFRS rules allow them to recognize unrealized earnings, they are likely to pay dividends from such earnings as well. However, as unrealized earnings are liable not be realized in the future, distribution based on them exacerbates the conflict of interest between creditors and shareholders. The research examines whether distributions from unrealized earnings increase default risk above and beyond distributions of realized earnings.

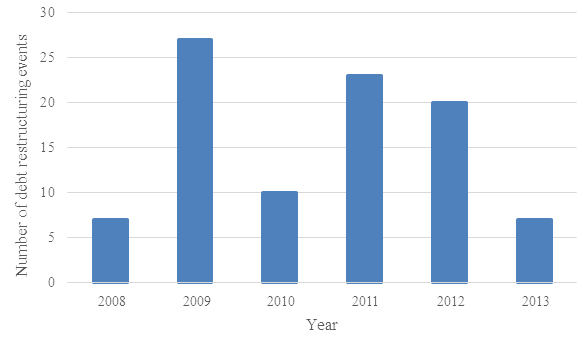

The sample used in the study consists of Israeli public companies that adopted the IFRS standards in 2007. As in many of the countries that adopted them, in Israel as well the Companies Law allows a company to distribute dividends from accounting earnings, and does not distinguish between realized and unrealized earnings—that is, it refers to them in the same manner. As it is impossible to ascertain the source of the dividends distributed, the researchers used a stringent criterion to identify the companies that distributed dividends from unrealized earnings: a company only meets the criterion if the amount of dividends it distributed is greater than all the realized earnings that it can distribute. (The criterion is based on the assumption that a company distributes all realized earnings before it distributes any unrealized earnings.) The study’s sample included 292 companies with tradable debt (bonds), of which 75 (approximately one-quarter) distributed dividends from unrealized earnings, and 94 of which (approximately one-third) went through a debt restructuring proceeding at least once during the sample period, the six years between 2008 and 2013.

Debt restructuring proceedings in the economy, 2008–13

Multivariate survival analysis using a relative hazard model (Cox 1972) yielded a positive and very statistically significant link between distribution of dividends from unrealized earnings and the risk of the company defaulting in the subsequent years: when comparing a company that distributed dividends from unrealized earnings to a similar company that did not distribute such dividends, it is found that the probability of the former to require a debt restructuring is more than three times greater, ceteris paribus. Additional examinations showed that the findings do not derive solely from ex ante riskier companies choosing to distribute dividends from unrealized earnings before encountering perceptible difficulties (that is, difficulties that are also reflected in financial data controlled for in the research).

If creditors suspect that the company is taking advantage of fair value accounting to increase its dividend distribution on the basis of “paper” profits, they can reprice the debt accordingly and demand a higher yield ex ante. However, the research finds that they do not do so: ceteris paribus, the cost of the debt for companies that distributed dividends from unrealized earnings—a cost reflected in bond yield spreads or in bond ratings—is not significantly different from the cost of the debt for companies that did not distribute such dividends.

As noted, the research found that the distribution of dividends from unrealized earnings significantly increases the probability of encountering financial distress, and that rating agencies and investors are not pricing this correctly. These findings indicate that bond market investors need to demand, at issuance, covenants that limit the ability of companies to distribute dividends from unrealized earnings, or at least to demand a higher yield on bonds of a company that distributed such dividends. Alternatively, the relevant regulators may need to limit such distributions. The findings of the research may lend support for the proposal of the Ministry of Justice and the Israel Securities Authority to amend the Companies Law, with the goal of preventing the distribution of dividends from unrealized earnings.

Full research (Hebrew)

Full research (Hebrew)